In 1970, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (the Corps) seized land belonging to the Native American Winnebago Tribe. Unfortunately, this turn of events was nothing new. The tribe had long suffered at the hands of the U.S. government.

Originally, the tribe lived in the lands of central Wisconsin and northern Illinois, fishing and hunting along its rivers and lakes, including Lake Winnebago. To make room for miners and other settlers, the U.S. government forcibly removed the tribe to various locations, including South Dakota, as many as 11 times throughout the 19th century.

The tribe, desperate for a permanent home, finally won the right to resettle. And following the Treaty of 1865, most settled on a reservation along the Missouri river near the Nebraska-Iowa border. The government promised the Winnebago Tribe this new land forever.

But in 1970, the government broke that promise..

Through eminent domain, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers took 1,600 acres of Winnebago reservation land for a proposed recreation project. Work on that project never began, but the Winnebago land remained under the control of the Corps.

In the 50 years since, the Winnebago Tribe has fought relentless legal battles to regain what is rightfully theirs. And while the tribe recovered the Nebraska portion of its reservation in 1985, the Iowa portion remained under governmental control for decades.

Until now.

Since 2017, leaders in Congress introduced bills to return that property to its rightful owners. But those bills went nowhere, and the issue remained unresolved.

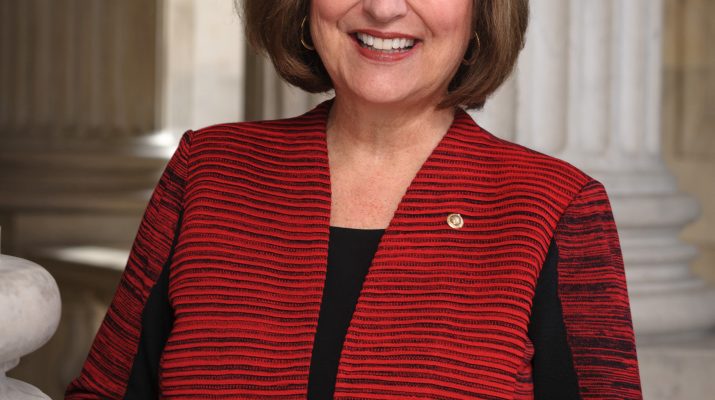

Last year, I introduced the Winnebago Land Transfer Act in the Senate. My bill transfers legal responsibility of the tribal lands from the Corps of Engineers to the Bureau of Indian Affairs to hold in trust for the tribe.

But passing the bill was no easy task.

Because the reservation extends across Nebraska and Iowa, we had to secure the support of Senators Grassley and Ernst in the Senate. Senator Ricketts co-sponsored our bill, and Representative Feenstra introduced the legislation in House. Working together, we secured the support of the entire Iowa and Nebraska delegations.

From there, we worked closely with the Senate Indian Affairs Committee to move the bill through the legislative process. I requested a hearing, invited the Chair of the Winnebago Tribe, Chairwoman Kitcheyan, to speak, and asked the Committee to approve it for full Senate consideration.

Once it passed out of committee, the Senate approved the legislation unanimously.

Thanks to the unending dedication of the Winnebago tribe and the work of my colleagues, the president signed the Winnebago Land Transfer Act into law last week.

Americans are taught that our country values justice and stays true to its word. And yet, our government did not live up to these ideals in its dealings with the Winnebago Tribe. In fact, it did the complete opposite.

Despite our nation’s past mistakes, we often have the chance to right old wrongs. And when those opportunities arise, we must take them. Today, we can be proud that after many, many years, the Winnebago tribe’s land has been restored.

Thank you for participating in the democratic process. I look forward to visiting with you again next week.