“Don’t touch that trailer yet,” G.O. advised. “A guy from the school is supposed to come by and pick out some cardboard.” Well, our recycling center manager always has a lot of irons in the fire as I, and others, on second shift arrive. Must be an art art project I thought as I found something else to do than bale that particular stack.

An hour or so later a man driving a sedan with out-of-town plates pulled up. “What do you have for us?” was our question. As he asked about the cardboard G.O. mentioned, I realized that I had seen this guy before: Steven Tamayo from the Alliance Arts Council posters hung on local business windows. His public program at the Performing Arts Center was that evening and he was looking for sheets of cardboard a bit bigger than poster board though still small enough for his trunk. We found over a dozen that fit the bill. The artist in residence thanked us and said the pile should be enough for his purposes.

Tamayo stopped by on a recent Friday. My wife and I had been planning a date night for that day and attended his AAC program. I told her about the cardboard and was anxious to see how he and the fourth graders taking part would use the repurposed material.

Alliance Arts Council presents a slate of performing artists every year, traditionally with an artist in residence and static exhibit at the Carnegie Arts Center. For 2021-22, Tamayo shared his culture and heritage as a traditional Sicangu Lakota whose family originates from the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota, according to the AAC event booklet. He spent a week presenting at assemblies in our schools and worked closely with fourth grade students.

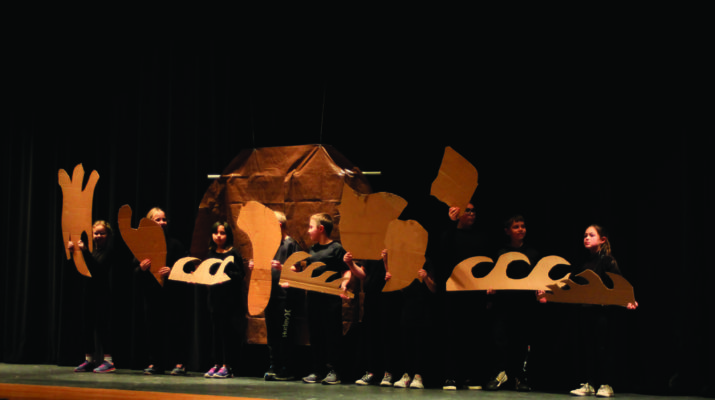

Early in the public program, about 10 students joined Tamayo on stage holding what had become of the cardboard. Each piece was cut into the shape of a continent. The children held the shapes together as Tamayo told the Lakota story of Pangaea, moving apart to show how the world changed to the present day. Trees, a spider and other supporting set pieces cut from the cardboard also appeared in that scene and others.

Tamayo provides “meaningful programming to the community that enriches their understanding of the history and cultural traditions of Native American people of the Great Plains” through his non-profit venture Bluebird Cultural Initiative.

I am always impressed with the dedication of these visiting artists and their passion to share and educate. Individuals like Tamayo, in particular, open a window into a culture students (and the public in general) may know little about. Fourth grade in Nebraska includes the state’s history as part of the curriculum. Though Native Americans figure in what they’re taught, students can learn so much more from first-person experiences such as Tamayo’s.

Attending a country school about five miles outside of Alliance, it was not much of a stretch for me to imagine what the fields and Sandhills along the southern horizon looked like more than a century before. We learned about Westward Expansion, the Native Americans who lived here then and white settlement that started in earnest when the railroad arrived.

Learning, however, builds in layers. Years go on with history and social studies classes filling in from an academic perspective. Then you meet people coming to know a bit of their culture and background as well. A museum exhibit here, an old man’s story there, friendships, articles read and over the years knowledge grows.

Will a collection of cardboard shapes register in the memories years later of the children who crafted them? I hope so. It was a blessing to help a visiting artist.