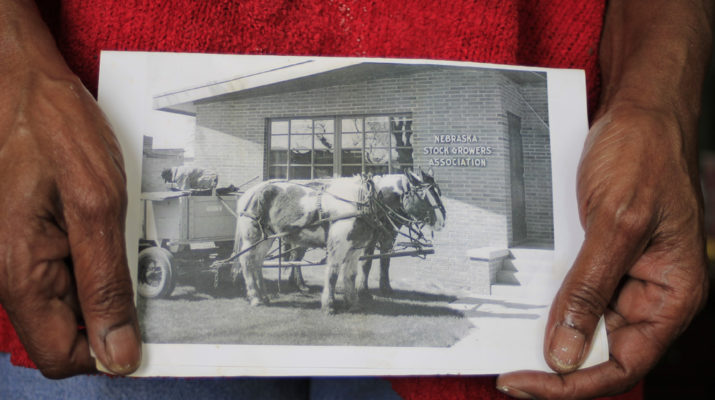

Clomp, clomp, clomp . . . eight hooves in rhythm always joined by the sound of metal rims rolling. Children’s ears would catch the familiar cadence as a few boys and girls jumped onto the back of Hayes Chandler’s wagon to ride for a block, maybe two.

Mention Hayes to Alliance natives around retirement age now, and riding that horse-drawn wagon immediately comes to mind. Florence Nickens, Hayes’ granddaughter, recalled, “In the early ‘50s kids started having birthday parties (where) they got to ride the wagon all afternoon and have a party on the wagon.”

Eventually, Hayes gave up using just the wagon. Nickens said he was probably 64 when he bought a pickup truck.

Despite his stature, six-foot-three with a size 15 wedding band, and almost always being on his garbage route or en route to a landscaping job, children never received a reprimand or cross word for hitching a ride. “He was the quiet, big man,” Nickens said. “A very gentle, loving man. He never lost his temper, or showed his anger.”

Growing up with her granddad and grandma Florence, Nickens described their character and cooperation as a couple. “I have a tendency to believe the people who work together, strive together . . . Taught you the Lord was there and He was good. Grandma read the Bible morning and night – showed us you can always get something new from it. They taught us a lot about respect and that money wasn’t everything.”

Respect is something everyone desires. As the Civil Rights Movement gained momentum in America, Hayes’ was embraced by his customers while some Alliance businesses and establishments still refused or restricted service to African Americans, Native Americans and other minorities. On a daily basis, Hayes picked up garbage from downtown businesses in addition to other addresses. He could be found planting lawns and landscaping.

“I’m surprised. For being a farmer and doing things other people wouldn’t do, he was so respected,” Nickens said. As an example, she mentioned the Elks Club (then just north of the post office), which wouldn’t allow black members. “But, when he picked up (their garbage) they’d have him come in and have a few drinks at the bar.”

I would have liked to see Hayes prepare a garden or transform a property in a few days with his horses and implements instead of the modern, high-tech equipment a contractor now brings to bear. Places such as the First Baptist Church at Tenth and Yellowstone are testaments to his work. Hayes’ career was all about two of the objectives of Keep Alliance Beautiful – litter prevention, and beautification & community improvement.

Hayes also helped maintain his neighborhood by buying lots for the city taxes, Nickens noted. He would then maintain and rent out the homes. “He was not a poor man, he was a working man,” she said.

Memories and words remain after a person passes away. Hayes died Dec. 14, 1966, he was 84. Sitting down to interview Nickens, she brought over a few of his awards and commendations. The Alliance Chamber of Commerce presented Hayes the Cornerstone Award for outstanding citizenship on Jan. 31, 1963. The Dale Carnegie Alumni Association bestowed its Good Human Relations award in 1965 during Good Human Relations Week.

“He was something special to the town as he was to his family and friends,” she said. “. . . I’m glad he’s my grandfather.”