By Rebecca Svec

Flatwater Free Press

Gary Barker seemed like one of the lucky ones.

At 21, he survived a surprise attack by North Vietnamese forces that filled his back and shoulder with shrapnel. After emergency surgery in Saigon and months recovering at a Denver hospital, the decorated soldier returned to his young family and the life he left in Kimball.

But the headaches began when Gary was 26. He didn’t make it past 28. An autopsy after his abrupt death revealed a tumor had formed on the brain stem, resulting from shrapnel left in his body.

Gary Barker had made it home from Vietnam. But the war took him just the same.

It seemed there would be no more milestones for his short life – until earlier this year when a letter arrived from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund. Now nearly 50 years after his death, a group of Gary’s family members, including his widow Barb Barker, and sister, Janice Kirchhoff, will stand on the east knoll of the memorial in Washington, D.C., on Saturday as Gary’s name is read aloud along with 566 others.

The reading is part of the Memorial Fund’s In Memory ceremony, an event recognizing Vietnam veterans who returned home and later died as a result of their service. The names of 17 other Nebraskans also will be read during the ceremony.

Gary’s widow and sister expect to feel a mix of pride and emotions tamped down decades ago.

“I never thought I would live long enough to see those who died after getting back to the states be recognized,” said Kirchhoff, of Lincoln.

Gary’s family has always been proud of his service and the honors he earned, including the Purple Heart, Vietnam Service Medal with Bronze Silver Star, National Defense Service Medal, Vietnam Campaign Medal and the Marksmanship Badge with Rifle Bar. The upcoming public recognition, though, takes it to another level.

It also takes them back.

For Kirchhoff, it draws out the memories of a little brother six years her junior, a slender and blond southeast Nebraska farm kid. She and Gary bonded over horses.

His calm, compassionate nature made him good with all the animals on their family farm between Palmyra and Bennet, but especially with horses. When he and their parents, Merle and Helen, moved to Kimball, Gary competed in rodeos, and planned to become a farrier. The draft letter changed his plans.

Barb remembers the new boy who showed up at Kimball High School her junior year. He was tall, serious for his age and determined.

“He wouldn’t leave me alone,” she recalled with the hint of a laugh. “I finally went on a date with him on a dare. We were together ever since.”

Barb liked Gary’s happy-go-lucky nature, the way he teased her. He always seemed upbeat.

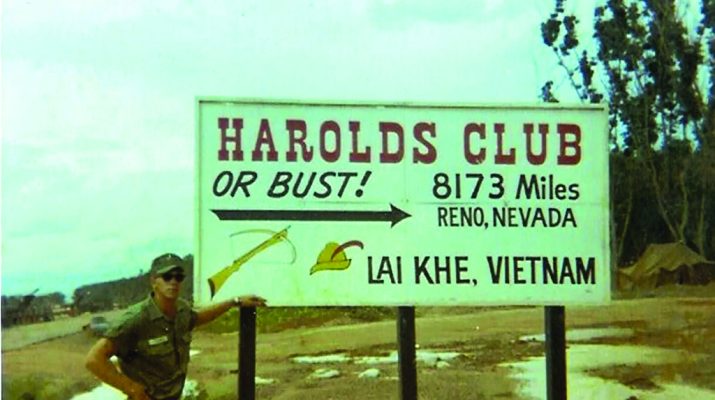

They married May 1, 1966. Gary was drafted into the U.S. Army May 17. After boot camp in Texas, he went to Fort Belvoir in Virginia to train with the 20th Engineer Brigade. Barb joined him there for a few months. Their son, Jerry, was born shortly before Gary began his tour in Vietnam in January 1967.

They lived their first year of marriage through letters. She wrote every day and mailed homemade brownies or treats weekly.

Gary had 23 days left in his deployment when the Tet Offensive, a coordinated attack striking numerous targets in South Vietnam, started.

Two days later on Feb. 2, Gary was jarred awake by a surprise attack near Saigon where he was positioned. He was knocked into a foxhole, with shrapnel sprayed into his shoulder, arm and back.

Surgeons took an artery from his groin area and put it in his arm to save his life, Barb said. The deep shoulder wounds damaged nerves, leaving his left arm a lesser version than the one he arrived in Vietnam with.

He returned to the states for healing and rehabilitation at Fitzsimons General Hospital in Denver. He remained on a ward there for nearly eight months, with occasional visits from family and weekend trips home.

Barb still remembers the injured soldiers who lined a hospital hallway waiting for an open bed. “It was heart wrenching,” she said.

More than 58,200 U.S. service members died and 153,303 were non-fatally wounded in Vietnam, according to the Department of Defense. Of the dead, 396 were from Nebraska.

When Gary returned to Kimball for good, he had basically lost the use of his stiff left hand. He did not dwell on it or let it stop him from working, driving a maintainer and trucks for the county roads department.

He never discussed his time in Vietnam with Barb. The Fourth of July was visibly tough for him, she remembers, but even on that day he kept quiet.

She appreciates the next few years they had together, adding two more babies, daughters Kerry and Sherry, their young family growing up together on an acreage near Kimball.

Then Gary started to change. One symptom followed the next: trouble concentrating, debilitating headaches, loss of balance. Getting through a workday took every ounce of his energy, Barb said. Sometimes, he would “fly off the handle over nothing,” which was out of character.

He went to the Cheyenne Hospital for tests in July 1975. While taking X-rays, Gary’s health deteriorated quickly. He died after a brief time in the intensive care unit.

“It was a total shock to me,” his sister recalled, her mind going back to the phone call that delivered the news.

“Dad had called the night before and said they were going to do tests in the morning. I didn’t know the severity of any of it.”

It would take an autopsy for the family to learn that Gary was another victim of the Vietnam War.

The lines of his obituary couldn’t convey the depth of the hole his family was left to fill.

It became Barb, their 8-year-old son and two daughters, ages 5 and 2. They stayed on the acreage in Kimball. Barb was grateful for the practical things Gary taught her. Change oil. Fix a mower. Cut tree branches.

She buried their daughter, Kerry, who died in a car crash at 27.

Barb believes there was a little sign from Gary when one of their granddaughters was born on July 23, the same day Gary had died.

Barb never remarried. She never met the right man who could be a father figure in the eyes of her children.

People didn’t ask as many questions then as they do now, Barb said. The recent attention regarding Gary’s upcoming honor has shown her that few people realized he had died from a war wound.

“People have read about it and then told me ‘I didn’t know,’” she said.

Since the In Memory program was created in 1993, more than 6,000 veterans have been added to the program’s honor roll, according to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund. A plaque memorializing their service was dedicated on the memorial grounds in 2004.

The program is submission-driven, meaning family members apply to have their loved one added.

Kirchhoff read a notice about the program in the Lincoln Journal Star and wondered if her brother would qualify.

A few months later, Barb saw the same information in a local paper. She gathered the needed service details and sent off an application. The confirmation letter arrived a short time later.

“I was emotional,” Barb said. “It just pulled at my heartstrings.”

Both she and Kirchhoff appreciate what the In Memory program is providing to their family and veterans like Gary: recognition, gratitude and a better understanding of the true numbers lost to a war that perhaps raised as many questions as it answered.

“It was so political … for kids like Gary, in the Midwest, so far removed from politics, they had to think ‘What am I doing in Vietnam? What was I in this for?’” Kirchhoff said.

Now Gary’s family members are gathering in Washington. They include Barb and her children, Sherry Barker Winstrom and Jerry Barker, and daughter-in-law Christy Barker. Kirchhoff and her husband, Leroy, their son, Ryan, and her stepmother, Louise Hagstrom Barker, also will attend.

They hope to meet some of the families of the 17 other Nebraska Vietnam veterans being honored. Kirchhoff expects a rush of emotions, much like she felt when she visited the memorial years ago and saw the overwhelming list of names, lives turned to letters on black granite.

As the 2023 honoree’s names are read aloud, Gary’s family will be attuned and waiting to hear the words of affirmation: Gary Adelbert Barker.

The Flatwater Free Press is Nebraska’s first independent, nonprofit newsroom focused on investigations and feature stories that matter.