Hemingford to Alliance via Highway 2 requires just under a half hour door to door, or enough dashboard time to hear a few songs or a short podcast. A week ago, when I returned the cardboard trailer to Hemingford I noticed how fast their residents fill two totes with plastic then happened to tune in to hear a show on the way back on National Public Radio titled “Is this ancient process the future of plastics recycling?”

The daily program, On Point, featured a type of chemical recycling called pyrolysis, a process that uses high heat under controlled conditions to separate components, some of which can become new plastic. Plastics that begin their journey to a new water bottle, for example, at the Keep Alliance Beautiful Recycling Center will undergo mechanical recycling.

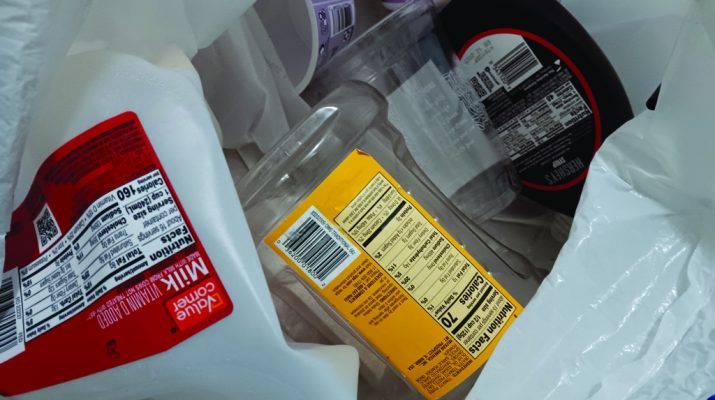

Before speculating on the potential of a chemical method, I went back and looked at how KAB fits in the more traditional process. Prior to joining the staff at our local Keep America Beautiful affiliate, the recycling center crew devoted a significant amount of time sorting plastic as we only accepted No. 1 PET (polyethylene terephthalate) and No. 2 HDPE (high-density polyethylene). That changed several years ago to anything labeled No. 1-7 as well as pliable plastics such as grocery bags, unlabeled smaller pieces, such as bottle caps, styrofoam and other formerly nonrecyclable types of plastic accepted by the Hefty Energy Bag program. All plastic is sorted before being baled to glean items that may have food or dirt residue or are not accepted, such as PVC. We also separate milk jugs, an undyed form of HDPE.

Bales of mixed plastic and orange bags (and sometimes other plastics such as grain totes or car parts) go first to Western Resources Group in Ogallala then to Firststar Recycling in Omaha. Milk jugs travel to Sandhill Plastics in Kearney. Machines break the bales apart again for further sorting, in the case of No. 1-7. Then workers shred and wash the hundreds, often thousands of items that had been together. Each type of plastic is then melted and pelletized before being melted again in the manufacture of new products.

Both mechanical and chemical recycling methods, such as pyrolysis, seek to address humanity’s plastic habit – however the number of times is limited, unlike alternatives like glass and aluminum. We are using more and more plastic every year with fewer than 10 percent recycled in the U.S. annually and a current global rate approaching 500 million tons produced a year. On Point cited the potential of current pyrolysis when starting off with 100 pounds of plastic trash as “maybe 15% to 20% of that ends up as new plastic.” The broadcast earlier put the efficiency of mechanical recycling at 50-80 percent.

Plastic waste is detrimental to the environment and even our health as the material breaks down and has made its way into our bodies. Consumers should reduce their use of plastic whenever possible. Buy products made of or with an alternative and more sustainable material. This “R” has been lost on the industry that produces plastic. Even though oil, gas and plastics corporations promote recycling they refuse to reduce or even slow the amount of new plastic introduced every year. Reusable water bottles, for instance, could save hundreds of disposable/one use bottles over their lifetimes. And, importantly, continue to recycle. Far more than 80 percent of the plastic we see at KAB goes down the line. Higher recycling rates overall will help keep the plastic that has already been produced away from littering the streets and filling the landfill.